Kiki's Delivery Service and the Relatable Catastrophes of Growing Up

This week, I'm wrong about how Miyazaki avoids chosen-one coming-of-age tropes in his classic film, plus I get way too invested in whether or not Kiki is gay

On a recent trip to Seattle, arriving at a friend’s beautiful apartment in Queen Anne, a picturesque neighborhood on a hill near the downtown, I looked at the multilayered view of charming houses and the bay on a cozy, rainy day and remarked that it felt like Kiki’s Delivery Service.

“What’s Kiki’s Delivery Service?” My friend asked. After briefly recovering from that remark on a fainting couch, I insisted she fly to Brooklyn so I could cook her and her boyfriend dinner and show her the movie.1

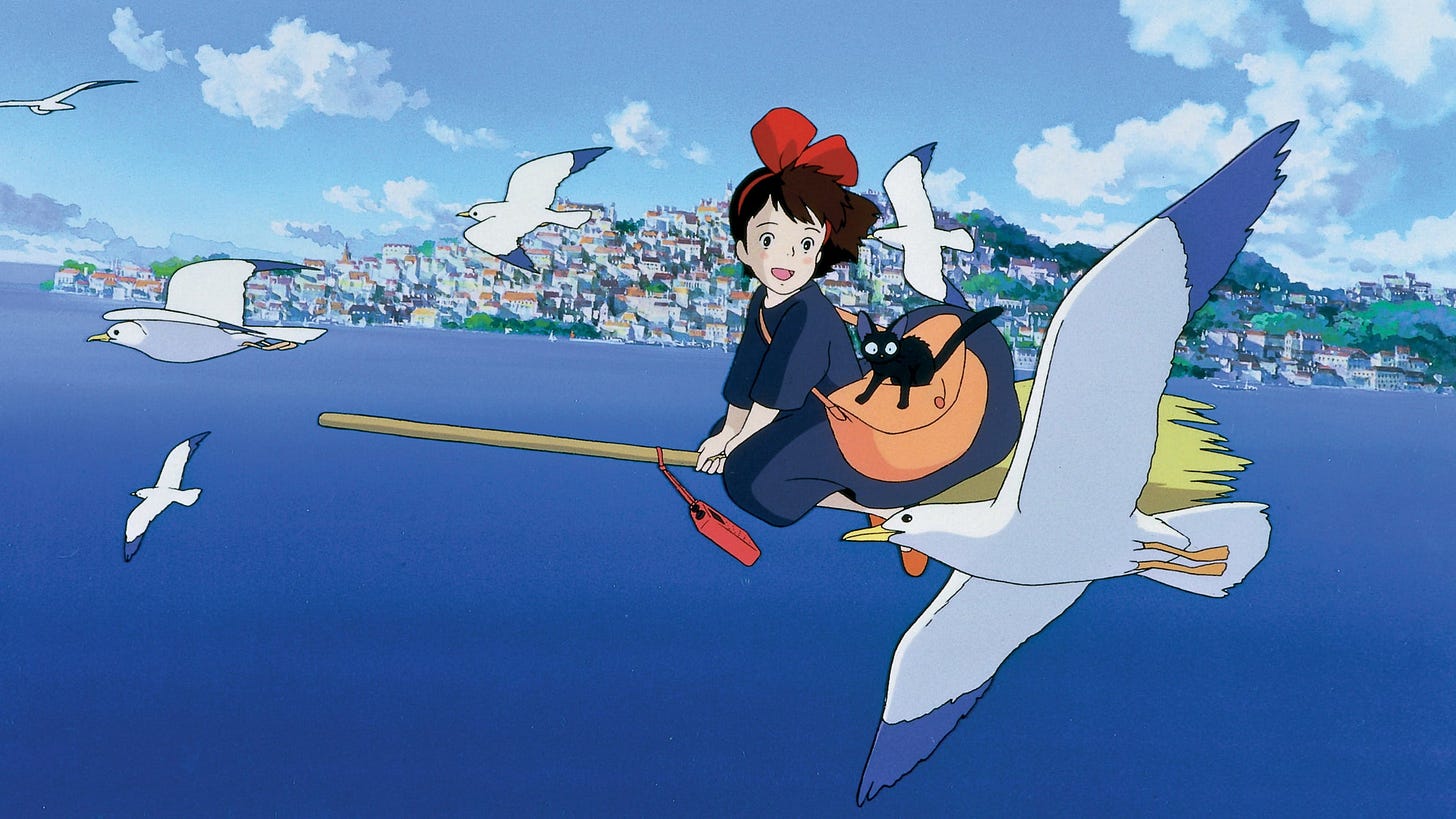

The film centers on Kiki, a young witch who just turned thirteen, who must travel to a new city and support herself for a year (everyone knows this a witchly tradition. The movie certainly won’t stop and explain it to you. Don’t question it). She starts a delivery service while living in the attic of a local bakery after making friends with the nicest woman/baker to ever live. She delivers some items and works through a crisis of confidence while making new friends along the way. That’s the entire plot. It’s unbearably charming.

Rewatching the film, I was reminded of several things: one, this movie is extremely gay (more on that later). Second, despite being among the most optimistic Miyazaki films I’ve seen, it still effectively blends subtle tragedy into its entire story and conclusion.2 Third, it’s another example of how Miyazaki doesn’t care at all about rigid rules or world-building and allows a story to grow and shape its scope however it needs to, making the movie’s world seem enormous and textured and mysterious rather than neat and “well structured,” which I wrote about last year. One of the best scenes of the film involves Kiki falling asleep in a train car full of hay, and being awakened by a cow licking her foot through netting below her. There’s a whimsy and patience storytelling-wise in that moment that you just don’t see in many western films, or films generally.

But what stood out most was how the film differs from pretty much every other fantasy coming of age story of the last 40 years. From Harry Potter to Percy Jackson, and even in darker stories like The Hunger Games, the coming of age story is centered around the protagonist being special—especially good at something, or having an ability no one else does, and coming to terms with that power and ability and the responsibility it gives them. Katniss is a brilliant archer and fighter and becomes the symbol of a revolution. Harry survives the killing curse and has special wizardly abilities as a result. Percy is the most powerful of the special, powerful demigods. Their growth is mediated through their exceptionality; they are inherently better and more gifted than those around them in some crucial way. Because these protagonists are so special, the fate of the world revolves around their decisions and achievements.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is a similar coming of age fantasy story that also centers on a young girl with special powers. But what makes the story so great is Kiki is TERRIBLE at everything that makes her special. She has no witch powers except for talking to her cat and flying, and she’s not very good at that either—she begins and ends the movie only tentatively in control of her broomstick, crashing and nearly-crashing into trees, buildings, and moving vehicles. She never delivers a single item without some kind of disaster occurring on the way. She is actively unexceptional. And because the movie isn’t about the future savior of the world/chosen one, the stakes of Kiki’s delivery service are, for the most part, adorably small. Will she deliver a pie in the rain? Will she be late for a party? Can she find a cat-shaped doll she dropped in the woods?

Kiki’s general incompetence as a witch isn’t a fulfillment of childhood fantasy as much as an embodiment of what it’s like to be a burgeoning young adult—to constantly try your best and still create disasters, to break things, to fail repeatedly, to feel like you have no idea how to do anything that other people seem to know how to do without trying.

And that makes Kiki’s victories a result not of some innate, unique trait—but a result of her sincere effort and friendliness. Kiki just tries really hard. She eagerly helps everyone she meets without expecting a reward. She accepts generosity when given to her, but with active thankfulness.

The movie takes pains to contrast her to other children. We only meet a few other young people in the movie, but they are universally brats. The one other young witch we meet is an obvious mean girl. Kiki delivers gifts to two young children who show no appreciation for their relatives’ generosity, are rude and dismissive to Kiki, and who demand their every whim be met by their parents. They are abrasive and portrayed with obvious disdain by the film. The one exception is Tombo, Kiki’s not-actually-love interest (more on that later), who is a mirror of Kiki’s positivity and kindness.

The climax of the film centers not on Kiki learning how to be a great witch, but on deciding to be a witch—in other words, to be herself—despite the fact that she’s really bad at it. She saves the day in a disaster because she’s willing to try to save Tombo even though she’s barely keeping her broom off the ground.

I think this is a somewhat radical message to give kids in this world—and one they need (and most adults need) to hear. Most kids are not exceptional at anything! Even when children are talented at something, they almost always lack the experience or vision or maturity to achieve greatness. And that’s OK! Even as adults, we’re lucky if we’re above average at even a couple of things—let alone great.

As a former teacher and still-educator—most young people today are not getting the chance to fail. They are not getting the chance to take pride in who they are—even, and especially, when they’re unexceptional. Our society’s helicopter parenting, nearly universal surveillance, and total lack of trust in children’s resilience and grit has made the independence and autonomy necessary for that productive failure to occur nearly impossible. Being OK at something is seen as a fundamental failure; being considered great is too often considered a right rather than an unlikely achievement won through long-term struggle. That long-term struggle is seen as an imposition rather than as something worthwhile in its own right.

Chosen-one stories too easily feed this sense of unearned, inherent superiority. They can also feed into the hyper-individuality that’s currently fraying every aspect of our world—telling us we deserve what we have without effort, that we owe nothing—even civility and kindness—to the people in our communities, in our countries, in our world. Miyazaki condemns that exact feeling: the bratty children in the movie believe they are the main character, and that being the main character entitles them to whatever they want. If I am the main character, why should I care what’s happening to other people as long as I’m getting the success and adoration I deserve? I’m the only person who really matters. And when I don’t receive those unearned rewards, how can I take out my anger on those I decide are responsible?

I don’t think these toxic tendencies are new, just magnified by our modern environment, and I think Miyazaki was responding to this way of seeing the world when he made Kiki’s Delivery Service. Kiki’s story tells kids that success isn’t being better than other people, but being willing to try, and fail, and try again, especially when what they are trying to do enriches and supports the people around them. He’s telling them they can take chances, can make mistakes, and trust each other’s support to continue on with their lives and together create a better, happier world. He’s telling them they are important even when they aren’t actually special. He’s telling them they are capable of thriving through the challenges that come with true autonomy and risk.

To put it simply: young people today are told they’re exceptional but also precious snowflakes—Kiki’s Delivery Service tells them they’re probably bad at everything but if they try hard anyway, they’ll be fine and end up happier for it. That’s a message we all need to hear.

Now for the Subtext—Kiki is Gay

When I first watched Kiki’s Delivery Service, I was overwhelmed by what seemed to me to be the obvious lesbian subtext. It felt clear to me it was more than a coming-of-age movie, but specifically a coming out movie made commercially viable for a late 80’s audience.

When I shared my reading with one of my best friends, a Japanese woman who has also seen a lot more Miyazaki, and understands the cultural context he worked in much more than I do, I was surprised by how much she pushed back. She said she saw the movie as presenting numerous examples of how to be a powerful woman—Kiki’s mom as a successful witch, the young artist she meets in the woods who helps Kiki recover her confidence, the baker who provides her with housing and support (and whose silent husband is an A1 Himbo)—but didn’t think Miyazaki was trying to say anything about queerness, especially given the culture of Japan in 1989.

I could make a Death-of-the-Author argument that Miyazaki’s intent doesn’t actually matter, but I don’t want to. I think Miyazaki meant for there to be queer subtext, and in the true spirit of this blog, I’m going to make that argument even though it’s probably wrong.

Here is the evidence, as I see it, for Kiki as a burgeoning lesbian (I’m also not the only person to have this thought, and I happened upon this tweet while researching for this post):

The movie goes out of its way, immediately, to have her childhood friends tell Kiki that she might meet a cute boy on her trip. They all giggle and she immediately changes the subject.

In the early parts of her journey, Kiki meets two people her age. One is another witch, just a little bit older than her, who acts very aloof and dismissive of Kiki. The other is Tombo, who immediately tries to get to know Kiki with a somewhat clumsy enthusiasm and admiration. Who does Kiki approach with the nervous trepidation of novice flirtation, ignoring her barbed comments? The other witch. And who does she treat with naked hostility? Tombo. In fact, she only warms to Tombo when he establishes his interest in her as a friend, rather than a romantic interest. They never have any sort of romantic moment.

This is a good time to point out that witches and lesbians have long-running historical connections. Miyazaki directly references several other historical stereotypes about witches—their connections, to cats, crows, etc.—and he would have certainly been aware of the queer connotations of witchcraft.

Kiki’s most prominent customer in the film, who she instantly connects to, is Madame. Madame, an older woman, lives alone in a large house with her maid Barsa, with whom she shares a loving, playful relationship. No mention of any husband past or present is made. History will say they were roommates.

The character who Kiki reacts to in a way that most matches an adolescent crush? Ursula, the artist who lives alone in the woods and paints and who invites Kiki to stay with her in the midst of her personal crisis. When Kiki arrives at her home a second time, she sees a vibrant, sensual painting that takes her breath away—and Ursula shares that the painting was inspired by Kiki. She asks Kiki to model for her. Spending the night at Ursula’s is the start of Kiki’s reconnection with her powers and identity. The subtext feels obvious, but in case you were wondering, if you google “lesbian Kiki’s Delivery Service” on google this is the first result.

Ursula is also misidentified as a boy a few scenes earlier by a truck driver, which she responds to by indignantly saying something along the lines of “with these legs??”

Given that the movie sets up the expectation of her meeting a male romantic interest in the opening scene, and she does meet a boy in Tombo who could absolutely fill that role, why does the movie not offer any sort of hint in that direction? Why does all of her crush-like behavior revolve around girls?

That’s the end of my subtextual analysis—but I did notice one more funny detail while rewatching the film. The ending credits play over a series of clips showing each character continuing with their lives. We see Kiki fly with Tombo (him in a plane, her on a broom) and him setting up a sign for her business, but their interactions keep them physically separate—we DO see her dropping off flowers to a girl her age! And in the FINAL shot of the film where Kiki is with another person, we see Kiki hanging out at the counter NOT with a character we’ve seen before (like Tombo, who would make total sense), but with another girl! A girl we’ve never seen before! A girl who, I dare suggest, is queer-coded! Who, perhaps, is acting in a flirtatious manner while leaning across the counter!

So maybe I’m going insane. But in my head, Kiki is gay, this is a story about her embracing that, and Miyazaki was an ally way ahead of his time. I rest my case.

I made fried chicken, a recipe I’ve been perfecting over the last few years and which I’ve now Pavloved myself into associating with Miyazaki. I’ve cooked it with Howl’s Moving Castle, Princess Mononoke, and Kiki’s Delivery Service (now twice). I love when food gets somewhat incomprehensibly linked to unrelated media in my mind—General Tsao’s Chicken will always say Star Wars on VHS to me, for example.

Specifically—during Kiki’s crisis of confidence, she loses the ability to speak with her best friend and cat, Gigi. Even when she regains her sense of self at the end of the movie, that ability never returns. There’s a beautiful and tragic message here about how growth is necessary, but inherently comes with loss. Growing up means giving up parts of who you are to become more realized in others. That’s another challenging, important message kids need to hear.

I really appreciate your commentary on growing up and accepting that you can still have a good life without being exceptional, and how many YA stories don’t allow for that in the hero. I also appreciate your message about mutuality rather than individualism. I haven’t seen the movie yet, but I guess it’s time!

I have a DVD of every Miyazaki/Studio Ghibli movie that is available in the United States. I believe the number is 21. I have never made an effort to look beyond the animation like you have (except superfically) because the animation is so breathtaking, Consequently, I appreciate your analysis. But I do look at his images as an artist myself (of sorts) and to see countless references to the art world. When KIki visits Ursula at her cabin and is able to view the large painting she is working on - well, that is an homage to Marc Chagall and for years that image has been imprinted on the front of my brain. Just thinking about it takes my breath away. Of course most of his movies ( and those of his associates) take my breath away. With a few exceptions.